JEFF GAMMAGE, INQUIRER STAFF WRITER

LAST UPDATED: Thursday, February 27, 2014, 11:01 PM

POSTED: Thursday, February 27, 2014, 9:40 PM

The kidnappers wouldn't stop writing.

They didn't send just one ransom note. Or two. Or 10. They sent 23, a veritable

War and Peace of demands.

But no money was paid. And the little boy they took was never seen again.

The case described as America's first recorded kidnapping for ransom took place in Philadelphia - the daylight abduction of 4-year-old Charley Ross from the front yard of his Germantown home in 1874. The quiet, shy boy was lured into the clutches of strangers by an offer of sweets, his fate believed to have given rise to the warning, "Never take candy from strangers."

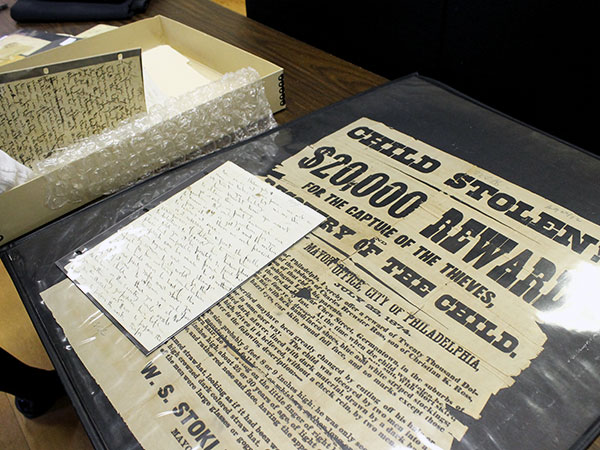

Friday night, a reception at the Germantown Historical Society opens a two-month-long exhibit on the case, tied to the recent surprising discovery of the ransom notes in the basement of a Mount Airy home.

The exhibit includes photos of the main actors, newspaper stories of the day, a missing-child poster, and more to fuel theories on the nature of a dark crime.

"It was the JonBenet Ramsey case of its time," said Barbara Hogue, executive director of Historic Germantown, an alliance of area museums.

And not just because it went unsolved.

News coverage of the kidnapping was sensational and national, torment to a city government preparing to host the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876 and urging people to open spare rooms to visitors.

The criminals struck upon a simple idea: Don't take people's property, take people. And get their families to pay for their return. It proved an enduring and replicable crime.

Kidnappers took and killed the infant son of aviator Charles Lindbergh in 1932, a case that journalist H.L. Mencken called "the biggest story since the Resurrection." Frank Sinatra Jr. was kidnapped from Harrah's Lake Tahoe in 1963, released when his father paid $240,000. John Paul Getty III was snatched in 1973 by kidnappers who demanded $17 million - and sent his severed ear to a newspaper when the family was slow to pay.

The Ramsey saga began the day after Christmas 1996, when mother Patsy found a ransom note on a staircase of the family home. The body of the 6-year-old beauty queen was discovered hours later in the basement.

As for the Charley Ross case, it began July 1, 1874, as the boy and his nearly 6-year-old brother, Walter, played outside.

A horse-drawn carriage pulled up, and two men inside offered to buy candy and fireworks if the boys would go for a ride. All four traveled to a store in Kensington, where Walter was given money and sent inside. The carriage then left without him.

Three days later, a letter demanding $20,000 reached the boys' father, a dry goods merchant, Christian Ross. That sum was a fortune at the time, the equivalent of more than $400,000 today.

"Mr Ros, be not uneasy, you son charley bruster be all writ we is got him and no powers on earth can deliver out of our hand," the kidnappers wrote.

On that July 4, as news of the crime spread, Mayor William Strumberg Stokley laid the cornerstone of the new City Hall in what was then Center Square, and officially broke ground for the centennial celebration in Fairmount Park. The Philadelphia Zoo had opened for the first time only three days earlier.

Detective work was relatively new. The Philadelphia Police Department was less than 40 years old, and the Pinkerton Detective Agency, which became involved in the search for the boy, had been formed less than 25 years earlier.

All during July, a frightened public demanded answers. The mayor offered a city reward of $20,000 - the same amount sought by the kidnappers. The Inquirer offered a reward, too. Children sent coins to help save the lost Charley.

The early ransom notes gave instructions for how Christian Ross should reply in the personal ads of local newspapers. Later, the kidnappers discussed the news coverage, attempting to justify their actions in increasingly desperate tones.

"I really do think they intended to give the child back once they got the money," said Carrie Hagen, author of

We Is Got Him: The Kidnapping That Changed America and a speaker at Friday night's reception. "I don't think they had any clue this would blow up like it did."

Police told Christian Ross not to pay the ransom, because they feared a wave of copycat crimes. Ross took the advice. He never saw his child again.

The letters stopped in November, after a series of arranged meetings fell through.

Authorities identified two suspects, career criminals Bill Mosher and Joe Douglas. In December the two were met by armed neighbors when they tried to rob a Brooklyn, N.Y., home. Mosher was killed in the shoot-out, but Douglas lingered for an hour, during which witnesses said he confessed, telling them, "I helped to steal Charley Ross. . . ."

The next year a suspected accomplice, a friend of Mosher's and a former Philadelphia police officer named William Westervelt, went on trial for kidnapping. Convicted of the lesser offense of conspiracy, he served seven years, then disappeared from history.

Charley's body was never found. One explanation? Maybe he wasn't killed, but placed in a different family, where he grew up unaware of his true identity. At the time, scores of "Orphan Trains" were headed west, taking neglected children in New York to new homes elsewhere. A child could easily have been slipped aboard.

"It's a sad story," Hagen said, "but one of the things about it, a positive outcome, was, a lot of children who were taken were found. You had people coming forward saying, 'My neighbor has a kid, and I don't know where the kid came from.'"

For decades after the crime, people stepped forward, hundreds of them, claiming to be Charley Ross. In the 1930s, a carpenter in his 60s named Gustave Blair persuaded an Arizona court that he was Charley Ross, successfully changing his name to that of the child. The Ross family dismissed his claims.

Today the case is largely forgotten, and the ransom notes thought lost - until March, when a Germantown Academy librarian found them in the basement of her Mount Airy home.

Bridget Flynn and a daughter were searching through boxes of family photos and letters, looking for a drawing that could appear on a bridal-shower invitation. As they rummaged, Flynn found a stack of small envelopes tied with a black shoelace.

"I thought they were love letters between my grandmother and my grandfather," Flynn said.

They weren't. But how the letters came to her home is a mystery. While her family has been in Philadelphia since the 1600s, there's no obvious connection to the Ross family or the case, Flynn said.

In November the notes were bought at auction by an anonymous benefactor, who then loaned them to Historic Germantown. The sale price was $20,000, the same as the ransom.

Texts of the letters have been available from newspapers and books of the era, but the exhibit marks the first time all 23 can be seen in public.

"There's still a lot of questions," Hogue said. "It's still not solved."

jgammage@phillynews.com 215-854-4906

@JeffGammage