Shirley Temple Dies at 85

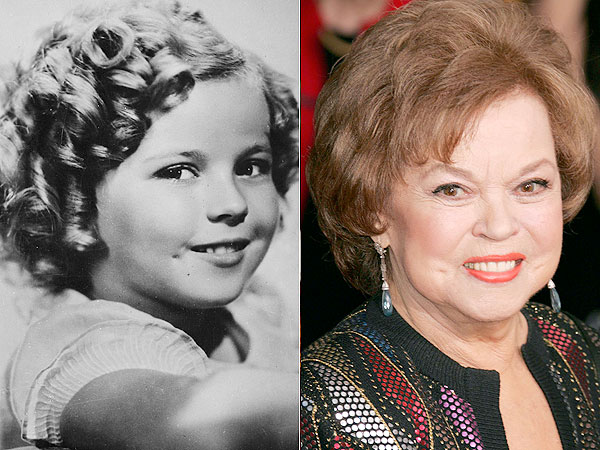

The adult and child Shirley Temple, beloved star

KAZEN/REX; AP

Shirley Temple, the dimpled, curly-haired child star who sang, danced, sobbed and grinned her way into the hearts of Depression-era moviegoers, has died, according to publicist Cheryl Kagan. She was 85.

Temple, known in private life as Shirley Temple Black, died at her home near San Francisco.

A talented and ultra-adorable entertainer, Shirley Temple was America's top box-office draw from 1935 to 1938, a record no other child star has come near. She beat out such grown-ups as Clark Gable, Bing Crosby, Robert Taylor, Gary Cooper and Joan Crawford.

In 1999, the American Film Institute ranking of the top 50 screen legends ranked Temple at No. 18 among the 25 actresses. She appeared in scores of movies and kept children singing "On the Good Ship Lollipop" for generations.

Temple was credited with helping save 20th Century Fox from bankruptcy with films such asCurly Top and The Littlest Rebel. She even had a drink named after her, an appropriately sweet and innocent cocktail of ginger ale and grenadine, topped with a maraschino cherry.

Temple blossomed into a pretty young woman, but audiences lost interest, and she retired from films at 21. She raised a family and later became active in politics and held several diplomatic posts in Republican administrations, including ambassador to Czechoslovakiaduring the historic collapse of communism in 1989.

"I have one piece of advice for those of you who want to receive the lifetime achievement award. Start early," she quipped in 2006 as she was honored by the Screen Actors Guild.

But she also said that evening that her greatest roles were as wife, mother and grandmother. "There's nothing like real love. Nothing." Her husband of more than 50 years, Charles Black, had died just a few months earlier.

They lived for many years in the San Francisco suburb of Woodside.

Temple's expert singing and tap dancing in the 1934 feature Stand Up and Cheer! first gained her wide notice. The number she performed with future Oscar winner James Dunn, Baby Take a Bow, became the title of one of her first starring features later that year.

Also in 1934, she starred in Little Miss Marker, a comedy-drama based on a story by Damon Runyon that showcased her acting talent. In Bright Eyes, Temple introduced "On the Good Ship Lollipop" and did battle with a charmingly bratty Jane Withers, launching Withers as a major child star, too.

She was "just absolutely marvelous, greatest in the world," director Allan Dwan told filmmaker-author Peter Bogdanovich in his book Who the Devil Made It: Conversations With Legendary Film Directors. ''With Shirley, you'd just tell her once and she'd remember the rest of her life," said Dwan, who directed Heidi and Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm. ''Whatever it was she was supposed to do - she'd do it. ... And if one of the actors got stuck, she'd tell him what his line was – she knew it better than he did."

Temple became a nationwide sensation. Mothers dressed their little girls like her, and a line of dolls was launched that are now highly sought-after collectables. Her immense popularity prompted President Franklin D. Roosevelt to say that "as long as our country has Shirley Temple, we will be all right."

"When the spirit of the people is lower than at any other time during this Depression, it is a splendid thing that for just 15 cents, an American can go to a movie and look at the smiling face of a baby and forget his troubles," Roosevelt said.

She followed up in the next few years with a string of hit films, most with sentimental themes and musical subplots. She often played an orphan, as in Curly Top, where she introduced the hit "Animal Crackers in My Soup," and Stowaway, in which she was befriended by Robert Young, later of Father Knows Best fame.

She teamed with the great black dancer Bill "Bojangles" Robinson in two 1935 films with Civil War themes, The Little Colonel and The Littlest Rebel. Their tap dance up the steps in The Little Colonel (at a time when interracial teamings were unheard-of in Hollywood) became a landmark in the history of film dance.

Some of her pictures were remakes of silent films, such as Captain January, in which she recreated the role originally played by the silent star Baby Peggy Montgomery in 1924. Poor Little Rich Girl and Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, done a generation earlier by Mary Pickford, were heavily rewritten for Temple, with show biz added to the plots to give her opportunities to sing.

She won a special Academy Award in early 1935 for her "outstanding contribution to screen entertainment" in the previous year.

"She is a legacy of a different time in motion pictures. She caught the imagination of the entire country in a way that no one had before," actor Martin Landau said when the two were honored at the Academy Awards in 1998.

Temple's fans agreed. Her fans seemed interested in every last golden curl on her head: It was once guessed that she had more than 50. Her mother was said to have done her hair in pin curls for each movie, with every hairstyle having exactly 56 curls.

On her 80th birthday, Temple received more than 135,000 presents from around the world, according to The Films of Shirley Temple, by Robert Windeler. The gifts included a baby kangaroo from Australia and a prize Jersey calf from schoolchildren in Oregon.

"She's indelible in the history of America because she appeared at a time of great social need, and people took her to their hearts," the late Roddy McDowall, a fellow child star and friend, once said.

Although by the early 1960s, she was retired from the entertainment industry, her interest in politics soon brought her back into the spotlight.

She made an unsuccessful bid as a Republican candidate for Congress in 1967. After Richard Nixon became president in 1969, he appointed her as a member of the U.S. delegation to the United Nations General Assembly. In the 1970s, she was U.S. ambassador to Ghana and later U.S. chief of protocol.

She then served as ambassador to Czechoslovakia during the administration of the first President Bush. A few months after she arrived in Prague in mid-1989, communist rule was overthrown in Czechoslovakia as the Iron Curtain collapsed across Eastern Europe.

"My main job [initially] was human rights, trying to keep people like future President Vaclav Havel out of jail," she said in a 1999 Associated Press interview. Within months, she was accompanying Havel, the former dissident playwright, when he came to Washington as his country's new president.

Her young life was free of the scandals that plagued so many other child stars – parental feuds, drug and alcohol addiction – but Temple at times hinted at a childhood she may have missed out on.

She stopped believing in Santa Claus at age 6, she once said, when "Mother took me to see him in a department store and he asked for my autograph."

After her years at the top, maintaining that level of stardom proved difficult for her and her producers. The proposal to have her play Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz didn't pan out. (20th Century Fox chief Darryl Zanuck refused to lend out his greatest asset.) And The Little Princess in 1939 and The Blue Bird in 1940 didn't draw big crowds, prompting Fox to let Temple go.

Among her later films were The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer, with Cary Grant, and That Hagen Girl, with Ronald Reagan. Several, including the wartime drama Since You Went Away, were produced by David O. Selznick. One, Fort Apache, was directed by John Ford, who had also directed her Wee Willie Winkie years earlier.

Her 1942 film, Miss Annie Rooney, included her first on-screen kiss, bestowed by another maturing child star, Dickie Moore.

After her film career effectively ended, she concentrated on raising her family and turned to television to host and act in 16 specials called Shirley Temple's Storybook on ABC. In 1960, she joined NBC and aired The Shirley Temple Show.

Her 1988 autobiography, Child Star, became a best-seller.

Temple had married Army Air Corps private John Agar, the brother of a classmate at Westlake, her exclusive L.A. girls' school, in 1945. He took up acting and the pair appeared together in two films, Fort Apache and Adventure in Baltimore. She and Agar had a daughter, Susan, in 1948, but she filed for divorce the following year.

She married Black in 1950, and they had two more children, Lori and Charles. That marriage lasted until his death in 2005 at age 86.

In 1972, she underwent successful surgery for breast cancer. She issued a statement urging other women to get checked by their doctors and vowed, "I have much more to accomplish before I am through."

Temple, known in private life as Shirley Temple Black, died at her home near San Francisco.

A talented and ultra-adorable entertainer, Shirley Temple was America's top box-office draw from 1935 to 1938, a record no other child star has come near. She beat out such grown-ups as Clark Gable, Bing Crosby, Robert Taylor, Gary Cooper and Joan Crawford.

In 1999, the American Film Institute ranking of the top 50 screen legends ranked Temple at No. 18 among the 25 actresses. She appeared in scores of movies and kept children singing "On the Good Ship Lollipop" for generations.

Temple was credited with helping save 20th Century Fox from bankruptcy with films such asCurly Top and The Littlest Rebel. She even had a drink named after her, an appropriately sweet and innocent cocktail of ginger ale and grenadine, topped with a maraschino cherry.

Temple blossomed into a pretty young woman, but audiences lost interest, and she retired from films at 21. She raised a family and later became active in politics and held several diplomatic posts in Republican administrations, including ambassador to Czechoslovakiaduring the historic collapse of communism in 1989.

"I have one piece of advice for those of you who want to receive the lifetime achievement award. Start early," she quipped in 2006 as she was honored by the Screen Actors Guild.

But she also said that evening that her greatest roles were as wife, mother and grandmother. "There's nothing like real love. Nothing." Her husband of more than 50 years, Charles Black, had died just a few months earlier.

They lived for many years in the San Francisco suburb of Woodside.

Temple's expert singing and tap dancing in the 1934 feature Stand Up and Cheer! first gained her wide notice. The number she performed with future Oscar winner James Dunn, Baby Take a Bow, became the title of one of her first starring features later that year.

Also in 1934, she starred in Little Miss Marker, a comedy-drama based on a story by Damon Runyon that showcased her acting talent. In Bright Eyes, Temple introduced "On the Good Ship Lollipop" and did battle with a charmingly bratty Jane Withers, launching Withers as a major child star, too.

She was "just absolutely marvelous, greatest in the world," director Allan Dwan told filmmaker-author Peter Bogdanovich in his book Who the Devil Made It: Conversations With Legendary Film Directors. ''With Shirley, you'd just tell her once and she'd remember the rest of her life," said Dwan, who directed Heidi and Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm. ''Whatever it was she was supposed to do - she'd do it. ... And if one of the actors got stuck, she'd tell him what his line was – she knew it better than he did."

Mother Shielded Her

Temple's mother, Gertrude, worked to keep her daughter from being spoiled by fame and was a constant presence during filming. Her daughter said years later that her mother had been furious when a director once sent her off on an errand and then got the child to cry for a scene by frightening her. "She never again left me alone on a set," she said.Temple became a nationwide sensation. Mothers dressed their little girls like her, and a line of dolls was launched that are now highly sought-after collectables. Her immense popularity prompted President Franklin D. Roosevelt to say that "as long as our country has Shirley Temple, we will be all right."

"When the spirit of the people is lower than at any other time during this Depression, it is a splendid thing that for just 15 cents, an American can go to a movie and look at the smiling face of a baby and forget his troubles," Roosevelt said.

She followed up in the next few years with a string of hit films, most with sentimental themes and musical subplots. She often played an orphan, as in Curly Top, where she introduced the hit "Animal Crackers in My Soup," and Stowaway, in which she was befriended by Robert Young, later of Father Knows Best fame.

She teamed with the great black dancer Bill "Bojangles" Robinson in two 1935 films with Civil War themes, The Little Colonel and The Littlest Rebel. Their tap dance up the steps in The Little Colonel (at a time when interracial teamings were unheard-of in Hollywood) became a landmark in the history of film dance.

Some of her pictures were remakes of silent films, such as Captain January, in which she recreated the role originally played by the silent star Baby Peggy Montgomery in 1924. Poor Little Rich Girl and Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, done a generation earlier by Mary Pickford, were heavily rewritten for Temple, with show biz added to the plots to give her opportunities to sing.

A Special Oscar

In its review of Rebecca, the show business publication Variety complained that a "more fitting title would be 'Rebecca of Radio City.' "She won a special Academy Award in early 1935 for her "outstanding contribution to screen entertainment" in the previous year.

"She is a legacy of a different time in motion pictures. She caught the imagination of the entire country in a way that no one had before," actor Martin Landau said when the two were honored at the Academy Awards in 1998.

Temple's fans agreed. Her fans seemed interested in every last golden curl on her head: It was once guessed that she had more than 50. Her mother was said to have done her hair in pin curls for each movie, with every hairstyle having exactly 56 curls.

On her 80th birthday, Temple received more than 135,000 presents from around the world, according to The Films of Shirley Temple, by Robert Windeler. The gifts included a baby kangaroo from Australia and a prize Jersey calf from schoolchildren in Oregon.

"She's indelible in the history of America because she appeared at a time of great social need, and people took her to their hearts," the late Roddy McDowall, a fellow child star and friend, once said.

Although by the early 1960s, she was retired from the entertainment industry, her interest in politics soon brought her back into the spotlight.

She made an unsuccessful bid as a Republican candidate for Congress in 1967. After Richard Nixon became president in 1969, he appointed her as a member of the U.S. delegation to the United Nations General Assembly. In the 1970s, she was U.S. ambassador to Ghana and later U.S. chief of protocol.

She then served as ambassador to Czechoslovakia during the administration of the first President Bush. A few months after she arrived in Prague in mid-1989, communist rule was overthrown in Czechoslovakia as the Iron Curtain collapsed across Eastern Europe.

"My main job [initially] was human rights, trying to keep people like future President Vaclav Havel out of jail," she said in a 1999 Associated Press interview. Within months, she was accompanying Havel, the former dissident playwright, when he came to Washington as his country's new president.

Movie Debut at 3

Born in Santa Monica to an accountant and his wife, Temple was little more than 3 years old when she made her film debut in 1932 in the Baby Burlesks, a series of short films in which tiny performers parodied grown-up movies, sometimes with risque results.Her young life was free of the scandals that plagued so many other child stars – parental feuds, drug and alcohol addiction – but Temple at times hinted at a childhood she may have missed out on.

She stopped believing in Santa Claus at age 6, she once said, when "Mother took me to see him in a department store and he asked for my autograph."

After her years at the top, maintaining that level of stardom proved difficult for her and her producers. The proposal to have her play Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz didn't pan out. (20th Century Fox chief Darryl Zanuck refused to lend out his greatest asset.) And The Little Princess in 1939 and The Blue Bird in 1940 didn't draw big crowds, prompting Fox to let Temple go.

Among her later films were The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer, with Cary Grant, and That Hagen Girl, with Ronald Reagan. Several, including the wartime drama Since You Went Away, were produced by David O. Selznick. One, Fort Apache, was directed by John Ford, who had also directed her Wee Willie Winkie years earlier.

Her 1942 film, Miss Annie Rooney, included her first on-screen kiss, bestowed by another maturing child star, Dickie Moore.

After her film career effectively ended, she concentrated on raising her family and turned to television to host and act in 16 specials called Shirley Temple's Storybook on ABC. In 1960, she joined NBC and aired The Shirley Temple Show.

Her 1988 autobiography, Child Star, became a best-seller.

Temple had married Army Air Corps private John Agar, the brother of a classmate at Westlake, her exclusive L.A. girls' school, in 1945. He took up acting and the pair appeared together in two films, Fort Apache and Adventure in Baltimore. She and Agar had a daughter, Susan, in 1948, but she filed for divorce the following year.

She married Black in 1950, and they had two more children, Lori and Charles. That marriage lasted until his death in 2005 at age 86.

In 1972, she underwent successful surgery for breast cancer. She issued a statement urging other women to get checked by their doctors and vowed, "I have much more to accomplish before I am through."

BOOKSHELF

Book Review: 'The Little Girl Who Fought the Great Depression' by John F. Kasson

She was America's biggest star. Then she turned 12—and got on with her life.

April 11, 2014 3:30 p.m. ET

Shirley Temple was what Charles Dickens jocularly called an "infant phenom," but in her case the world took the evaluation seriously. She herself was less impressed. "I class myself with Rin Tin Tin," the grown-up woman said. "People were looking for something to cheer them up. They fell in love with a dog and a little girl."

John F. Kasson's "The Little Girl Who Fought the Great Depression" seeks to analyze the reasons for her popularity and speculates on her relationship to the 1930s Depression. A cultural historian, Mr. Kasson links Temple to Franklin Delano Roosevelt through their use of media (her movies, his radio and newsreels) and their shared ability to flash their famous smiles. Roosevelt himself acknowledged her importance. "It is a splendid thing that for just 15 cents, an American can go to a movie and look at the smiling face of a baby and forget his troubles."

The Little Girl Who Fought the Great Depression

By John F. Kasson

Norton, 384 pages, $27.95

Norton, 384 pages, $27.95

Shirley Temple ca. 1934 Getty Images

Mr. Kasson devotes an entire chapter to Temple as an American commercial commodity, discussing mainly the popular Shirley Temple doll and the line of relatively expensive dresses that carried her name. There was in fact much more: sheet music, coloring books, cream pitchers, bookends, a costly playhouse with 7-foot walls and a porch, and the "Shirley Temple permanent," guaranteed to twist even the most stubborn little-girl hair into adorable corkscrew curls.

Shirley Jane Temple was born April 23, 1929, or so everyone believed, including her. She had actually been born in 1928, but one year was shaved off her age for publicity's sake. Unlike other young stars, such as Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney, Temple was not "born in a trunk." Her father was a Santa Monica bank teller, and her family lived in a modest California home. When Shirley was 3, Gertrude Temple enrolled her at a nearby dance studio, where she was spotted by scouts for a company that produced dubious one-reelers starring small children. Between 1931 and 1934, Temple made eight "Baby Burlesks," in which she danced, pouted, sang and sashayed around in costumes that were half-adult, half-child: tops that featured feather boas, hats, gloves, furs and jewelry, and bottoms that were diapers secured with gigantic safety pins.

By 1934, Temple was a 6-year-old veteran. Her big break came when she was given a small role in Fox Film's "Stand Up and Cheer!," a movie designed to reassure the public during the darkest days of the Depression. (The plot concerned the appointment of a "Secretary of Amusement.") Temple's showstopper includes an army of chorus girls, James Dunn singing "Baby Take a Bow" and Art Deco décor. When it's time for her entrance, Temple taps out onto the stage in a starched polka-dot dress, her golden curls bouncing and her dimples flashing. She smiles, she's confident, she's adorable and she can dance. Over the next six years, Temple was the most popular star in America, though once in a while someone dared speak critically: Adolphe Menjou, who played opposite her in "Little Miss Marker" (1934) said: "This child frightens me. She knows all the tricks."

Although Mr. Kasson's book is written to place Temple in the Depression-era context, he does not neglect her remarkable career. He presents an accurate picture of Hollywood's star system of the 1930s and her place in it, making the point that, although children on screen were often imitating adult behavior, their primary goal was to "perform childhood." Mr. Kasson is also droll about her acting style, which, he says, was learned in the Baby Burlesks, where she was taught to "arch her eyebrows, round her mouth in surprise, thrust out her lower lip, and cock her head sideways with a knowing smile." (She was also inspired by her mother's directive: "Sparkle, Shirley, sparkle!") Mr. Kasson credits 20th Century Fox head Darryl F. Zanuck, for fashioning a formula designed to appeal to Depression audiences: simple stories to lift spirits and promise happiness. "Keep her skirts high," he instructed. "Have co-stars lift her up whenever possible. . . . Preserve babyhood."

Seen today, the Temple films, unexpectedly, can deliver what they originally delivered. They are (and were) sentimental, child-worshiping stories with slight premises. What they have is what they had: Shirley Temple. She's feisty, funny and sassy. She has instructions for rule-bearing grown-ups ("oh, lay off me") and opinions on everything ("nix on that"). When things get too treacly, they are undercut by a wonderful song-and-dance number created specifically for her: "On the Good Ship Lollipop" ("Bright Eyes," 1934), "Animal Crackers in My Soup" ("Curly Top," 1935), the lovely "Goodnight, My Love" ("Stowaway," 1936).

During her dance down the streets of a fishing village (with Buddy Ebsen in "Captain January," 1936), she taps over rain barrels, stacked boxes and various stair levels, singing "At the Codfish Ball." In "Bright Eyes," which many feel is her best overall movie, the canny studio created a perfect foil for Temple's perfection in Jane Withers, who played a (very rich and very mean) little brat who menaces Shirley—a possible surrogate for anyone who wasn't buying the sweetness.

Inevitably, Shirley Temple faced what all child stars do: a short shelf life. When her 1940 "Blue Bird" fared poorly at the box office, her mother bought out the rest of her contract from Fox, declaring it was time for her daughter to lead "a normal life"; she was only 12. Although she was an exceptionally pretty teenager and had not lost her talent, Temple was no longer unique. She had a brief career in prestige films such as David O. Selznick's "Since You Went Away" (1944) and John Ford's "Fort Apache" (1948) and co-starred with Myrna Loy and Cary Grant in "The Bachelor and the Bobby Soxer " (1947). She made her final film, "A Kiss for Corliss," in 1949.

Mr. Kasson's chapter "What's a Private Life?" outlines what it meant for a child—and her family—to become a nation's obsession: the weird fan mail, kidnapping threats, mob scenes, lack of privacy and desperate fight to maintain some sort of normalcy. Gertrude Temple stoutly rejected the label of "stage mother" and always acted as if Temple's career were a larkish sideline to their regular lives. The Fox studio created a version of Temple's rise to fame that made it seem almost accidental, an inevitable result of an irrepressible talent. The public bought this myth. It gave them hope for their own lumpkin offspring and reassured them that Temple was not being exploited.

The question of whether any child star can ever lead an ordinary life is open to debate. One of the most insightful books about child stardom, "Twinkle Twinkle, Little Star (But Don't Have Sex or Take the Car)" (1984), was written by Dickie Moore, who began work in movies at the age of 5, became "a has-been at the age of 12" and later married another former child performer, Jane Powell. Mr. Moore identified common themes in the post-stardom life of Jackie Coogan, Margaret O'Brien, Natalie Wood and others, including Donald O'Connor and Temple herself. "I felt guilty and isolated; very shy," Natalie Wood told him. "There was no grown-up I could confide in."

Temple's own autobiography, "Child Star" (1988), is cheerfully upbeat yet surprisingly clear-eyed. Unlike other child stars, she seemed able to handle the fame and was a wry observer of her own phenomenon: "I stopped believing in Santa Claus at an early age," she recalled later. "Mother took me to see him . . . and he asked me for my autograph." As she worked day to day, there were no nervous breakdowns, no tantrums, and later in life no pills and booze. True, her first marriage was a disaster: In 1945, at age 17, she married actor John Agar, whose drinking became problematic. She divorced him on Dec. 5, 1950, and on Dec. 16 she married San Francisco businessman Charles Black, whom she'd met on a Hawaiian vacation. She was still only 21, and Black was wealthy and successful, so she no longer had to support herself and her family. Temple moved away from Hollywood, raised her family and kept busy with civic activities. She suffered no tragedies except for breast cancer, which she faced bravely and publicly. After a short venture into television in 1960, Temple left show business forever. In 1967 she entered another arena that some might call a variation on show business: politics.

Shirley Temple Black died in February of this year, age 85 (for real). Behind her were three successful careers: child star; wife and mother; and U.S. ambassador. A phenomenon as a child, she had also become a phenomenon as a woman, managing to accomplish the thing most people feel is impossible: having it all.

—Ms. Basinger is chairwoman of the department of film studies at Wesleyan University.

No comments:

Post a Comment