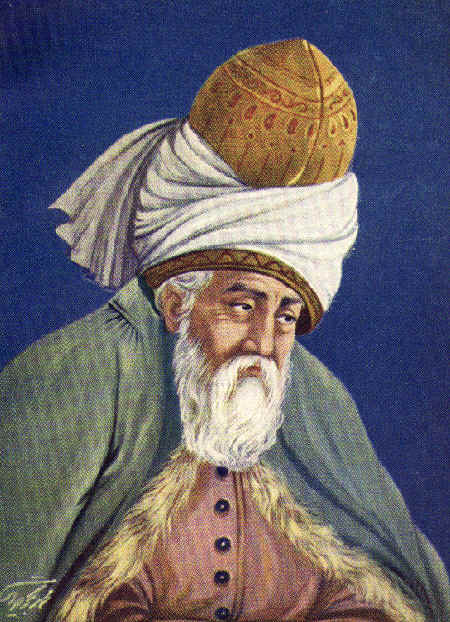

RUMI'S PORTRAIT

SCROLL DOWN FOR REVIEW OF "POEMS THAT MAKE GROWN MEN CRY"

Allspirit Poetry

Poems on Death, Dying and Grief

- Peace my heart...Rabindranath Tagore

- White Ashes...from Rennyo's Letters

- Because I could not stop for Death...Emily Dickinson

- Holy Sonnets X...John Donne

- The dead they sleep...Samuel Hoffenstein

- The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 21

- When I Am Dead, My Dearest...Christina Rossetti

- A Parable of Immortality - Henry Van Dyke

- On Death - Kahlil Gibran

- If Death is Kind...Sara Teasdale

- When I die...Rumi

- When a man knows God...Svetasvatara Upanishad

- Attitude toward Death...Tecumseh

- Zen Death Poems

- All Return Again...Ralph Waldo Emerson

Peace, my heart, let the time for the parting be sweet.

Let it not be a death but completeness.

Let love melt into memory and pain into songs.

Let the flight through the sky end in the folding of the wings over the nest.

Let the last touch of your hands be gentle like the flower of the night.

Stand still, O Beautiful End, for a moment, and say your last words in silence.

I bow to you and hold up my lamp to light you on your way.

Let it not be a death but completeness.

Let love melt into memory and pain into songs.

Let the flight through the sky end in the folding of the wings over the nest.

Let the last touch of your hands be gentle like the flower of the night.

Stand still, O Beautiful End, for a moment, and say your last words in silence.

I bow to you and hold up my lamp to light you on your way.

~Rabindranath Tagore

White Ashes from Rennyo's Letters

translated by Hisao Inagaki et al

When I deeply contemplate the transient nature of human life, I realize that, from beginning to end, life is impermanent like an illusion. We have not yet heard of anyone who lived ten thousand years. How fleeting is a lifetime! Who in this world today can maintain a human form for even a hundred years? There is no knowing whether I will die first or others, whether death will occur today or tomorrow. We depart one after another more quickly than the dewdrops on the roots or the tips of the blades of grasses. So it is said. Hence, we may have radiant faces in the morning, but by evening we may turn into white ashes. Once the winds of impermanence have blown, our eyes are instantly closed and our breath stops forever. Then, our radiant face changes its color, and the attractive countenance like peach and plum blossoms is lost. Family and relatives will gather and grieve, but all to no avail? Since there is nothing else that can be done, they carry the deceased out to the fields, and then what is left after the body has been cremated and has turned into the midnight smoke is just white ashes. Words fail to describe the sadness of it all. Thus the ephemeral nature of human existence is such that death comes to young and old alike without discrimination. So we should all quickly take to heart the matter of the greatest importance of the afterlife, entrust ourselves deeply to Amida Buddha, and recite the nembutsu. Humbly and respectfully.

BECAUSE I could not stop for Death--

He kindly stopped for me--

The Carriage held but just Ourselves--

And Immortality.

He kindly stopped for me--

The Carriage held but just Ourselves--

And Immortality.

We slowly drove--He knew no haste

And I had put away

My labour and my leisure too,

For His Civility--

And I had put away

My labour and my leisure too,

For His Civility--

We passed the School, where Children strove

At Recess--in the Ring--

We passed the Fields of Gazing Grain--

We passed the Setting Sun--

At Recess--in the Ring--

We passed the Fields of Gazing Grain--

We passed the Setting Sun--

Or rather--He passed Us--

The Dews drew quivering and chill--

For only Gossamer, my Gown--

My Tippet--only Tulle--

The Dews drew quivering and chill--

For only Gossamer, my Gown--

My Tippet--only Tulle--

We paused before a House that seemed

A Swelling of the Ground--

The Roof was scarcely visible--

The Cornice--in the Ground--

A Swelling of the Ground--

The Roof was scarcely visible--

The Cornice--in the Ground--

Since then--'tis Centuries--and yet

Feels shorter than the Day

I first surmised the Horses Heads

Were toward Eternity--

Feels shorter than the Day

I first surmised the Horses Heads

Were toward Eternity--

Emily Dickinson

Death be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadfull, for, thou art not soe,

For, those, whom thou think'st, thou dost overthrow,

Die not, poore death, nor yet canst thou kill mee.

From rest and sleepe, which but thy pictures bee,

Much pleasure, then from thee, much more must flow,

And soonest our best men with thee doe goe,

Rest of their bones, and soules deliverie.

Thou art slave to Fate, Chance, kings, and desperate men,

And dost with poyson, warre, and sicknesse dwell,

And poppie, or charmes can make us sleepe as well,

And better than thy stroake; why swell'st thou then?

One short sleepe past, wee wake eternally,

And death shall be no more; death, thou shalt die. .

Mighty and dreadfull, for, thou art not soe,

For, those, whom thou think'st, thou dost overthrow,

Die not, poore death, nor yet canst thou kill mee.

From rest and sleepe, which but thy pictures bee,

Much pleasure, then from thee, much more must flow,

And soonest our best men with thee doe goe,

Rest of their bones, and soules deliverie.

Thou art slave to Fate, Chance, kings, and desperate men,

And dost with poyson, warre, and sicknesse dwell,

And poppie, or charmes can make us sleepe as well,

And better than thy stroake; why swell'st thou then?

One short sleepe past, wee wake eternally,

And death shall be no more; death, thou shalt die. .

~John Donne

The dead they sleep a long, long sleep;

The dead they rest, and their rest is deep;

The dead have peace, but the living weep.

The dead they rest, and their rest is deep;

The dead have peace, but the living weep.

~Samuel Hoffenstein

Lo! some we loved, the loveliest and best

That Time and Fate of all their Vintage prest,

Have drunk their Cup a Round or two before,

And one by one crept silently to Rest.

That Time and Fate of all their Vintage prest,

Have drunk their Cup a Round or two before,

And one by one crept silently to Rest.

Translated by Edward FitzGerald

When I am dead, my dearest,

Sing no sad songs for me;

Plant thou no roses at my head,

Nor shady cypress tree:

Be the green grass above me

With showers and dewdrops wet;

And if thou wilt, remember,

And if thou wilt, forget.

I shall not see the shadows,

I shall not feel the rain;

I shall not hear the nightingale

Sing on, as if in pain:

And dreaming through the twilight

That doth not rise nor set,

Haply I may remember,

And haply may forget.

Sing no sad songs for me;

Plant thou no roses at my head,

Nor shady cypress tree:

Be the green grass above me

With showers and dewdrops wet;

And if thou wilt, remember,

And if thou wilt, forget.

I shall not see the shadows,

I shall not feel the rain;

I shall not hear the nightingale

Sing on, as if in pain:

And dreaming through the twilight

That doth not rise nor set,

Haply I may remember,

And haply may forget.

~Christina Rossetti

I am standing upon the seashore.

A ship at my side spreads her white sails to the morning breeze

and starts for the blue ocean.

A ship at my side spreads her white sails to the morning breeze

and starts for the blue ocean.

She is an object of beauty and strength,

and I stand and watch until at last she hangs

like a speck of white cloud

just where the sea and sky come down to mingle with each other.

Then someone at my side says,

" There she goes! "

and I stand and watch until at last she hangs

like a speck of white cloud

just where the sea and sky come down to mingle with each other.

Then someone at my side says,

" There she goes! "

Gone where?

Gone from my sight . . . that is all.

She is just as large in mast and hull and spar

as she was when she left my side

and just as able to bear her load of living freight

to the place of destination.

as she was when she left my side

and just as able to bear her load of living freight

to the place of destination.

Her diminished size is in me, not in her.

And just at the moment

when someone at my side says,

" There she goes! "

there are other eyes watching her coming . . .

and other voices ready to take up the glad shout . . .

when someone at my side says,

" There she goes! "

there are other eyes watching her coming . . .

and other voices ready to take up the glad shout . . .

" Here she comes! "

~Henry Van Dyke

Then Almitra spoke, saying, We would ask now of death.

And he said:

You would know the secret of death. But how shall you find it unless you seek it in the heath of life? The owl whose night-bound eyes are blind unto the day cannot unveil the mystery of light. If you would indeed behold the spirit of death, open your heart wide unto the body of life. For life and death are one, even as the river and sea are one.

In the depth of your hopes and desires lies your silent knowledge of the beyond; and like seeds dreaming beneath the snow your heart dreams of spring. Trust the dreams, for in them is hidden the gate to eternity.

Your fear of death is but the trembling of the shepherd when he stands before the king whose hand is to be laid upon him in honor. Is the shepherd not joyful beneath his trembling, that he shall wear the mark of the king? Yet is he not more mindful of his trembling?

For what is it to die but to stand naked in the wind and to melt into the sun? And what is it to cease breathing, but to free the breath from its restless tides, that it may rise and expand and seek God unencumbered?

Only when you drink from the river of silence shall you indeed sing. And when you have reached the mountain top, then you shall begin to climb. And when the earth shall claim your limbs, then shall you truly dance.

The Prophet

Kahlil Gibran

Walker & Company

Phoenix Press, 1923

Kahlil Gibran

Walker & Company

Phoenix Press, 1923

Perhaps if death is kind, and there can be returning,

We will come back to earth some fragrant night,

And take these lanes to find the sea, and bending

Breathe the same honeysuckle, low and white.

We will come back to earth some fragrant night,

And take these lanes to find the sea, and bending

Breathe the same honeysuckle, low and white.

We will come down at night to these resounding beaches

And the long gentle thunder of the sea,

Here for a single hour in the wide starlight

We shall be happy, for the dead are free.

And the long gentle thunder of the sea,

Here for a single hour in the wide starlight

We shall be happy, for the dead are free.

~Sara Teasdale

When I die...

When I die

when my coffin

is being taken out

you must never think

i am missing this world

when my coffin

is being taken out

you must never think

i am missing this world

don't shed any tears

don't lament or

feel sorry

i'm not falling

into a monster's abyss

don't lament or

feel sorry

i'm not falling

into a monster's abyss

when you see

my corpse is being carried

don't cry for my leaving

i'm not leaving

i'm arriving at eternal love

my corpse is being carried

don't cry for my leaving

i'm not leaving

i'm arriving at eternal love

when you leave me

in the grave

don't say goodbye

remember a grave is

only a curtain

for the paradise behind

in the grave

don't say goodbye

remember a grave is

only a curtain

for the paradise behind

you'll only see me

descending into a grave

now watch me rise

how can there be an end

when the sun sets or

the moon goes down

descending into a grave

now watch me rise

how can there be an end

when the sun sets or

the moon goes down

it looks like the end

it seems like a sunset

but in reality it is a dawn

when the grave locks you up

that is when your soul is freed

it seems like a sunset

but in reality it is a dawn

when the grave locks you up

that is when your soul is freed

have you ever seen

a seed fallen to earth

not rise with a new life

why should you doubt the rise

of a seed named human

a seed fallen to earth

not rise with a new life

why should you doubt the rise

of a seed named human

have you ever seen

a bucket lowered into a well

coming back empty

why lament for a soul

when it can come back

like Joseph from the well

a bucket lowered into a well

coming back empty

why lament for a soul

when it can come back

like Joseph from the well

when for the last time

you close your mouth

your words and soul

will belong to the world of

no place no time

you close your mouth

your words and soul

will belong to the world of

no place no time

~RUMI, ghazal number 911, translated May 18, 1992, by Nader Khalili.

"When a man knows God, he is free: his sorrows have an end,

and birth and death are no more. When in inner union he is

beyond the world of the body, then the third world, the world

of the Spirit, is found, where the power of the All is, and man

has all: for he is one with the ONE."

and birth and death are no more. When in inner union he is

beyond the world of the body, then the third world, the world

of the Spirit, is found, where the power of the All is, and man

has all: for he is one with the ONE."

From: Svetasvatara Upanishad

Live your life that the fear of death

can never enter your heart.

Trouble no one about his religion.

Respect others in their views

and demand that they respect yours.

Love your life, perfect your life,

beautify all things in your life.

Seek to make your life long

and of service to your people.

Prepare a noble death song for the day

when you go over the great divide.

Always give a word or sign of salute when meeting

or passing a friend, or even a stranger, if in a lonely place.

Show respect to all people, but grovel to none.

When you rise in the morning, give thanks for the light,

for your life, for your strength.

Give thanks for your food and for the joy of living.

If you see no reason to give thanks,

the fault lies in yourself.

Touch not the poisonous firewater that makes wise ones turn to fools

and robs the spirit of its vision.

When your time comes to die, be not like those

whose hearts are filled with fear of death,

so that when their time comes they weep and pray

for a little more time to live their lives over again

in a different way.

Sing your death song, and die like a hero going home.

can never enter your heart.

Trouble no one about his religion.

Respect others in their views

and demand that they respect yours.

Love your life, perfect your life,

beautify all things in your life.

Seek to make your life long

and of service to your people.

Prepare a noble death song for the day

when you go over the great divide.

Always give a word or sign of salute when meeting

or passing a friend, or even a stranger, if in a lonely place.

Show respect to all people, but grovel to none.

When you rise in the morning, give thanks for the light,

for your life, for your strength.

Give thanks for your food and for the joy of living.

If you see no reason to give thanks,

the fault lies in yourself.

Touch not the poisonous firewater that makes wise ones turn to fools

and robs the spirit of its vision.

When your time comes to die, be not like those

whose hearts are filled with fear of death,

so that when their time comes they weep and pray

for a little more time to live their lives over again

in a different way.

Sing your death song, and die like a hero going home.

The Teaching of Tecumseh

Ryonen:

When Ryonen was about to pass from this world, she wrote another poem:

Sixty-six times have these eyes beheld the changing scene of autumn. I have said enough about moonlight, Ask no more. Only listen to the voice of pines and cedars when no wind stirs.

Senseki: At last I am leaving: in rainless skies, a cool moon... pure is my heart

Banzan: Farewell... I pass as all things do dew on the grass.

Basho: On a journey, ill: my dream goes wandering over withered fields.

Nandai: Since time began the dead alone know peace. Life is but melting snow.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

It is the secret of the world that all things subsist and do not

die, but only retire a little from sight and afterwards return again.

Nothing is dead; men feign themselves dead, and endure mock funerals

and mournful obituaries, and there they stand looking out of the

window, sound and well, in some new strange disguise. Jesus is not

dead; he is very well alive; nor John, nor Paul, nor Mahomet, nor

Aristotle; at times we believe we have seen them all, and could

easily tell the names under which they go.

- See more at: http://www.allspirit.co.uk/dying.html#diedie, but only retire a little from sight and afterwards return again.

Nothing is dead; men feign themselves dead, and endure mock funerals

and mournful obituaries, and there they stand looking out of the

window, sound and well, in some new strange disguise. Jesus is not

dead; he is very well alive; nor John, nor Paul, nor Mahomet, nor

Aristotle; at times we believe we have seen them all, and could

easily tell the names under which they go.

Wall Street Journal:

BOOKSHELF

Book Review: 'Poems That Make Grown Men Cry,' edited by Anthony and Ben Holden

You don't need a degree in creative writing to be brought to tears by verse.

April 11, 2014 3:22 p.m. ET

Terry George, the Irish screenwriter and director, chokes up whenever he reads Seamus Heaney's "Requiem for the Croppies." The sonnet is an acutely condensed retelling of the 1798 Irish rebellion, a series of battles in which an army of mostly peasants—"the pockets of our greatcoats full of barley"—tried to throw off British rule. He's right; the last three lines, recalling the rebellion's final battle on June 21, catch in the throat:

The hillside blushed, soaked in our broken wave,

They buried us without shroud or coffin

And in August . . . the barley grew up out of our grave.

Mr. George is one of the 100 men Anthony and Ben Holden queried for their anthology of "Poems That Make Grown Men Cry." The editors aren't trying to make the case for poetry—perhaps a hopeless task in our time—but the book does it anyway. Poetry, so easily assumed to be merely weird self-expression since the death of rhyme and meter, isn't that at all: It's the arrangement of language into rhythmical structures to make it say what it can't say otherwise. The Holdens remind us that you don't have to be an academic or a postgraduate in creative writing to be moved by verse. Or, indeed, brought to tears by it.

Poems That Make Grown Men Cry

Edited by Anthony and Ben Holden

Simon & Schuster, 310 pages, $25

Simon & Schuster, 310 pages, $25

© ImageZoo/Corbis

The editor Harold Evans couldn't fight them back reading Wordsworth's "Character of the Happy Warrior" at a colleague's funeral. The critic Clive James sheds them for his parents at "Canoe" by Keith Douglas. The novelist Sebastian Faulks cries over Samuel Taylor Coleridge's "Frost at Midnight" (a marvelous poem—though not, I would have thought, one likely to induce tears). Despite the slight hokeyness of the whole idea, the overall effect is to make excellent poetry seem like what it is: a wholly accessible language with its own range of expression and its own pleasures.

The collection has its biases. Anthony Holden is a journalist and biographer, his son a writer and film producer, and the men included are mostly writers, academics, actors and filmmakers. Most of them are English, as the editors are, and consequently the poems are mostly British in provenance: W.H. Auden and Thomas Hardy are the favorites; Philip Larkin isn't far behind.

The vast majority of the poems reprinted here are not, as the title might suggest, mawkish or melodramatic. The best are haunting. The novelist Alexander McCall Smith names Auden's rather enigmatic lyric about unanswerable questions, "If I Could Tell You": "If we should weep when clowns put on their show, / If we should stumble when musicians play, / Time will say nothing but I told you so." But it quickly becomes clear that much of one's emotional response depends on the circumstances in which a poem is encountered. The actor Patrick Stewart's choice of Edna St. Vincent Millay's admittedly wonderful "God's World" has less to do with Millay's lines themselves, it seems, than with the way the poem reminds him of seeing a New England autumn for the first time ("Lord, I do fear / Thou'st made the world too beautiful this year").

A few of the poems are moving in their own right, with or without explanation. I had never read Robert Graves's "The Cool Web," submitted by the literary scholar John Sutherland, a near-perfect four-stanza meditation on the human need to explain away what scares or delights us: "There's a cool web of language winds us in, / Retreat from too much joy or too much fear: / We grow sea-green at last and coldly die / In brininess and volubility." If you have never read Randall Jarrell's "The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner," chosen here by the poet Paul Muldoon, be prepared.

Shakespeare's Sonnet 30 ("When to the sessions of sweet silent thought"), chosen by the writer and broadcaster Melvyn Bragg, isn't so wrenching as Jarrell's poem, but Mr. Bragg's short explanation makes the sonnet pierce to the heart. Shakespeare's reflections on the long-ago death of a friend remind Mr. Bragg "of my first wife, who took her life more than forty years ago. I feel as responsible, as guilty, and as ashamed now as I was then."

I defy anyone not to enjoy the Holdens' book: It's plain fun. But it has evangelistic potential as well. Two centuries ago our celebrities were not actors or singers but poets. Poetry has now all but disappeared from public life, with the consequence that we are cut off from an entire mode of thought—not unlike losing math or philosophy. Can it be revived? I don't know, but if a book full of lachrymose men can help, I'm for it.

—Mr. Swaim is writing a book on political language and public life.

Searchers

At dawn Warren is on my bed,

a ragged lump of fur listening to the birds as if deciding whether or not to catch one. He has an old man's mimsy delusion. A rabbit runs across the yard and he walks after it thinking he might close the widening distance just as when I followed a lovely woman on boulevard Montparnasse but couldn't equal her rapid pace, the cick-click of her shoes moving into the distance, turning the final corner, but when I turned the corner she had disappeared and I looked up into the trees thinking she might have climbed one. When I was young a country girl would climb a tree and throw apples down at my upturned face. Warren and I are both searchers. He's looking for his dead sister Shirley, and I'm wondering about my brother John who left the earth on this voyage all living creatures take. Both cat and man are bathed in pleasant insignificance, their eyes fixed on birds and stars. |

No comments:

Post a Comment