Why Beans Were an Ancient Emblem of Death

Fava beans can be lethal.

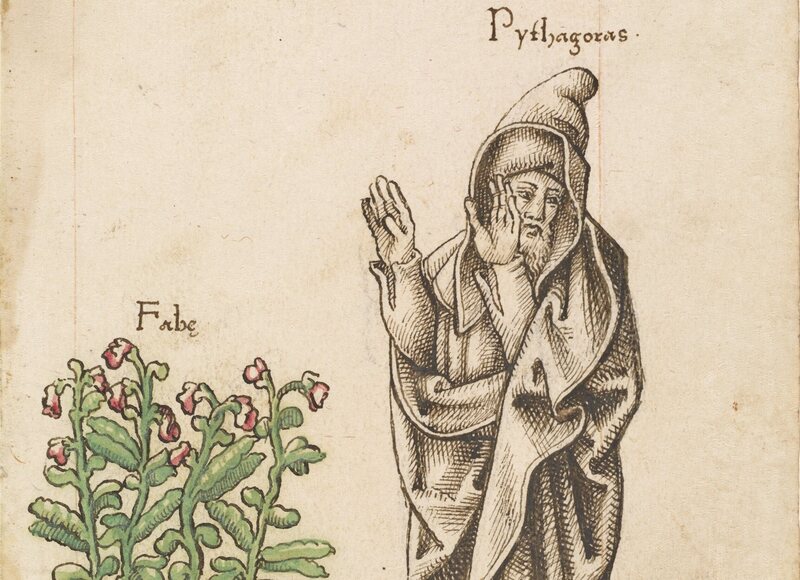

THE GREEK MATHEMATICIAN AND PHILOSOPHER Pythagoras, who you might remember from geometry class, had his very own cult. Followers lived communally, studied the cosmos, and ate vegetarian. But unlike today’s vegetarians, they also avoided beans. This wasn’t just a quirk. Like the Ancient Egyptians and Romans, they considered broad beans (also known as fava beans) a supernatural symbol of death. And due to a deadly allergy, the beans likely deserved their reputation.

Fava beans remain common in Greece, but other popular beans, such as green beans, kidney beans, and lima beans, only reached Europe and Asia after 1492. “When the word bean is used in European texts prior to 1492, it is almost always the fava,” writes food historian Ken Albala. Cultivated for millennia, they were an important source of protein across the classical world.

Despite being one of the first cultivated crops in history, many cultures had mixed feelings about favas. The Greek historian Herodotus wrote that Egyptians refused to cultivate beans at all. Though this was untrue, beans were often used for sacrifices, and in later Rome, priests of Jupiter couldn’t touch or even mention beans, due to their association with death and decay. For Roman funerary feasts, or silicernium, certain ritual foods were served: eggs, lentils, poultry, and favas.

Pythagoras’s aversion to beans, though, always got a lot of attention, even from ancient writers. According to Pliny, Pythagoreans believed that fava beans could contain the souls of the dead, since they were flesh-like. Due to their black-spotted flowers and hollow stems, some believers thought the plants connected earth and Hades, providing ladders for human souls. The beans’ association with reincarnation and the soul made eating fava beans close to cannibalism. Aristotle, writing earlier, went much further. One possible reason for the ban, he wrote, was that the bulbous shape of beans represented the entire universe. Nevertheless, other Greeks ate plenty of fava beans, and Pythagorean beliefs were mocked. The poet Horace tauntingly called beans “relations of Pythagoras.”

There’s also more earthly reasons to avoid beans. Diogenes Laertius, the Roman biographer of the Greek philosophers, wrote that beans were made of soul-stuff, much of which was present in humans. As it happens, the Greek word anemos means both “wind” and “soul.” Famously, beans are the magical fruit. Diogenes thought the excessive farting caused by eating too many fava beans was downright disturbing. Aristotle also thought that Pythagoreans abstained from beans as a political protest against democracy, since colored beans could be used to cast votes in elections (Pythagoreans favored oligarchy).

All symbolism aside, Pythagoras’s aversion to beans may have even contributed to his death. Legend has it he had to live in a cave for a time, to hide from a dictator. Some accounts of his death describe him fleeing attackers, who chase him until a field of flowering fava beans blocks his way. When he refuses to run any further, he’s killed.

This may seem ridiculous, but for certain people, a field of fava beans can spell certain death. Some researchers believe that historical suspicion about fava beans could be rooted in favism, a genetic disorder more common in the Mediterranean than anywhere else. Named for the triggering bean, people with favism develop hemolytic anemia from eating favas, or even inhaling the pollen from its flowers. After consumption or contact, red blood cells start to break down, which can cause anemia-like symptoms, jaundice, and even heart failure. Even today, one out of 12 people affected die of favism.

Perhaps Pythagoras had favism, or perhaps not. But the association between beans and somber rituals still exists: They are a Lenten meal in Greece and give name to the Italian All Soul’s Day cookie, fave del morti, or beans of the dead. Certainly, otherworldly beans give a whole new meaning to the requisite funeral three-bean salad.

No comments:

Post a Comment