Here Lies E. Coli

There’s a bunch of gross stuff, besides human bodies, hiding under graveyards.

4,374

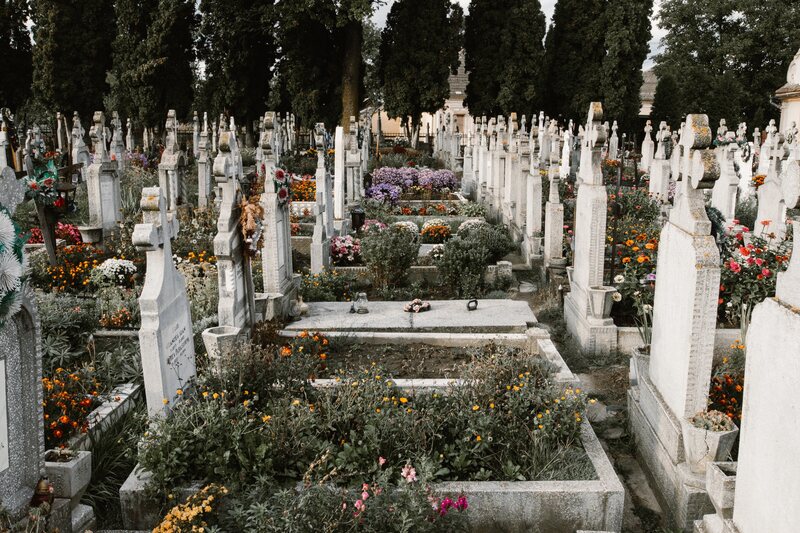

In the central cemetery of Marau, a small city in southern Brazil, squat mausoleums are crowded together like a mess of toy blocks. From the cobbled walks, the cemetery looks clean and well kept. But a couple of years ago, when a team of researchers visited, they noticed a crack in the wall of one of the tombs. Inside was a relatively new corpse, and it was leaking.

A human body is made mostly of water, carbon, and salts, containing calcium, potassium, iron, and other compounds familiar from the back of a vitamin bottle. When a person dies and their body starts to decompose, it transforms into a salty liquid—known as “necroleachate”—made up of about three-fifths water and two-fifths salts and organic compounds. Every 15 or 16 pounds of body weight produces a gallon of leachate, which has a distinct, fishy smell.

In cemeteries, this liquid of decomposition seeps into the ground and, especially in sandy or gravelly soil, can mix with the groundwater below. In Brazil, where it’s hot and humid and torrential, the risks of this happening are particularly high. “I consider cemeteries one of the biggest contamination problems,” says Alcindo Neckel, a geographer at Brazil’s Faculdade Meridional, who led the study of the Marau cemetery.

For millennia, groups of people have set aside special places to inter their dead, but as the world’s population has grown, so have the problems with concentrating dead bodies in this way. “Cemeteries can be regarded as special kinds of landfills,” the World Health Organization wrote in a 1998 report, and, like any landfill, they come with pollution risks. There have been few comprehensive studies of their environmental hazards, but in some cases—a cemetery that keeps flooding, for instance—the dangers of contamination are clear. With cemeteries sometimes converted into parks and playgrounds, or surrounded by dense development, environmental scientists are increasingly trying to understand the real dangers hidden in cemetery grounds.

In any place where we bury bodies, the soil will be different from the surrounding land, and those underground signatures can last for hundreds, even thousands, of years. Some researchers have a name for cemetery soils—“necrosols”—and they can carry higher concentrations of nutrients than the surrounding areas. Far more alarming are the microbes that soil can contain.

Back in the 19th century, there were at least a few documented cases of cemeteries contaminating urban water supplies. Cholera often slipped from dead bodies into drinking water, and in Berlin in the 1860s, people who lived near cemeteries were at higher risk of contracting typhoid fever. In Paris, the water near cemeteries might have tasted sweet and had that fishy, infected smell.

Modern cemeteries are full of all sorts of other potential contaminants. Every year in the United States, more than 100,000 tons of steel—“enough to rebuild the Golden Gate Bridge,” as a reporter for Modern Farmer noted—are buried in cemeteries, along with wood preservatives, paints, medical devices with radioactive components, zinc, silver, bronze, hip replacements, breast implants, and all the other detritus of human life that we take with us to the grave. Embalming fluids, which once included arsenic, are gradually mixed into the dirt. The formaldehyde used today is a carcinogen. Corpses secrete toxic compounds called putrescine and cadaverine, which are responsible for the off-putting smell of decomposition. Cemeteries are heavily landscaped, too, which means a lot of fertilizer. The varnishes of coffins, the clothing people are buried in, the make-up on their faces—it’s all filled with compounds that, concentrated heavily in one place, can become a hazard.

While human bodies decompose in about a decade, some of these pollutants linger for much longer. Traces of metals, for instance, can persist for many years. “It dilutes over time,” says Matthys Dippenaar, a hydrogeologist at the University of Pretoria, who has been leading a project on the environmental hazards of cemeteries. “But it never disappears.”

The way that cemeteries are sited and designed can exacerbate these issues, his project found. Graves can act like a sieve, providing channels for rain or floodwater to flow into the ground, directly through the highest concentrations of contaminants. Or the presence of a cemetery can lead to erosion, which sloughs the buried pollutants off into nearby water sources. Often cemeteries are located in flood-prone areas, close to wells, or in sensitive places, because as a form land use and compared to activities like housing and industry, Dippenaar says, “a cemetery is often wrongly considered to be the lowest risk.”

From a public health perspective, the contamination that poses the highest risk is the pathogens. “Historically, people have assumed if you put formaldehyde in the body, then you know the pathogens would die off,” says microbiologist Eunice Ubomba-Jaswa, a water resources quality manager at the South African Water Research Commission, and one of Dippenaar’s collaborators. But studies have found all sorts of microbes thriving in cemetery soil: E. coli, salmonella, C. perfringens (a common cause of foodborne illness), and B. anthracis (which, as its name suggests, carries anthrax). In laboratory simulations of cemetery conditions, Ubomba-Jaswa was surprised to find that E. coli survived the biocide that was supposed to kill them off. In one study, their team found E. coli, including the more dangerous, drug-resistant strains, in water samples from three different cemeteries.

Before we panic about the toxic waste sites in our midst, it’s important to remember that in most cases, there is no immediate danger or cause for alarm. But this research shows that cemeteries can be reservoirs for many things that we don’t want to live around. And the problem could get worse in the case of a serious disease outbreak, in which the infectious agents could simply cycle through cemeteries and back into the living population.

“It’s a very low probability of a very high risk,” says Dippenaar.

Researchers who study these issues, including Neckel, Dippenaar, and Ubomba-Jaswa, often come to the conclusion that burial is simply an unsustainable way to deal with dead bodies, in the long term. For a cemetery to be naturally secure, “you need the prime land, not the worst land,” says Dippenaar.

It’s not totally obvious what the best alternative is for an environmentally conscious death. Cremation, for instance, has its own environmental impact. But there are plenty of ideas floating around—from vertical cemeteries to mushroom death suits to freezing a body and shaking it to dust.

“The way we live has changed so rapidly, but how we die and how we look at burial has remained quite static over a long period of time,” says Ubomba-Jaswa. “We are changing our lifestyles, with respect to how we live, and that should keep up with how we die.”