An Artist for the Instagram Age

Is Yayoi Kusama’s new participatory-art exhibit about seeking profound experiences—or posting selfies?

Well before the Yayoi Kusama show

opened in Washington, D.C., I heard from total strangers that I would

not be able to get in. I heard about the lines, the waits, the tickets

that would be released in batches every Monday at noon, the need to make

arrangements now now now. The craze was on, though the exhibition was

still more than a month away. “Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors” was

starting its multicity tour at the Hirshhorn Museum. The circus was

coming to town.

Back in January, I knew that this

once-in-a-lifetime chance to see those half-dozen mirrored rooms—those

infinite dreamworlds for one, created by Yayoi Kusama, who is 88 and

lives by choice in a mental hospital in Japan—needed to be on my art

bucket list.Listen to the audio version of this article:Feature stories, read aloud: download the Audm app for your iPhone.

Much of the art on my list is designed to involve the observer in ways that no mere gallery-going ever could—and indeed makes the blockbuster exhibitions of the 20th century (Picasso, King Tut, the treasure houses of Britain) seem quaint. Yes, the long lines are still part of the experience, but new elements have been added. Cameras are often allowed, which opens the door to Instagram, Snapchat, and other social media. The visitor’s encounter is, in many cases, time-limited. Most important, many of the works on my bucket list invite the spectator to engage more personally with the art.

What’s that you say? You don’t have an art bucket list? Well, you can borrow mine. First, though, I should warn you that you have already missed many of the unmissable experiences I have had on my list.

Take New York alone. Kara Walker’s A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, a giant sphinx made of sugar, topped with a mammy head, is no longer at the Domino Sugar refinery on the East River (which has since been demolished). You can no longer see Cate Blanchett’s dramatic recitations of various art manifestos at the Park Avenue Armory. (However, her performance can now be seen as a movie, Manifesto.) You can no longer pay your respects, at the Episcopal Church of the Heavenly Rest on Fifth Avenue, to Sophie Calle’s dead mother by watching an 11-minute video of her death. Marina Abramović, the performance artist, is no longer available to sit with you at MoMA. You missed staying dry (or getting wet) in the Rain Room while MoMA had it. (Good news, though: The Los Angeles County Museum of Art recently acquired it for its permanent collection, so you might have another chance.) You cannot float nude in salt water at Manhattan’s New Museum in an “Experience” designed by Carsten Höller. Rirkrit Tiravanija isn’t making Thai curry for visitors at the David Zwirner gallery in Chelsea or at MoMA anymore. The chance to walk through Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s orange Gates in Central Park has long since passed. Sigh.

But cheer up, general public! Plenty of other can’t-miss art experiences aren’t going anywhere. I’m thinking of land art and site-specific art. Robert Smithson, for instance, created Spiral Jetty (1970) on the Great Salt Lake, in Utah, by arranging large rocks in a huge spiral. Michael Heizer made Double Negative (1969–70) near Overton, Nevada, by cutting two huge trenches into a mesa there. Walter De Maria composed The Lightning Field (1977) in the high desert of New Mexico by planting a vast field of 400 tall, lightning-attracting poles in a grid pattern. For the people who manage to make these treks, the dividend is not only the awesome sense of landscape transformed into art but also the keen realization that you and your journey are part of it.

If there is a

poster artist for the current participatory-art craze, it has got to be

Yayoi Kusama, whose exhibits—especially her Infinity Mirror rooms—have

drawn record crowds around the world for the past few years. In her

case, the challenge is not so much getting to the show, but getting into

the show, and then getting into each individual room in the show. After

you get your prized time slot—and good luck with that—you must wait

your turn in not just one line but six. Most of the Infinity Mirror

rooms can fit two or three people, and each has its own line to stand

in.

Luckily, as with any good amusement park, there are, along

with the main rides, plenty of other entertainments. At the Kusama show,

the side attractions amount to a more conventional museum experience: a

short course in Kusama’s early obsessional work—her repetitive nets,

polka dots, and phalluses. You will learn that it was by wrestling with

her mental illness and her compulsion to spread those forms on every

surface—walls, floors, furniture—that Kusama began to lay the groundwork

for the Infinity Mirror rooms.

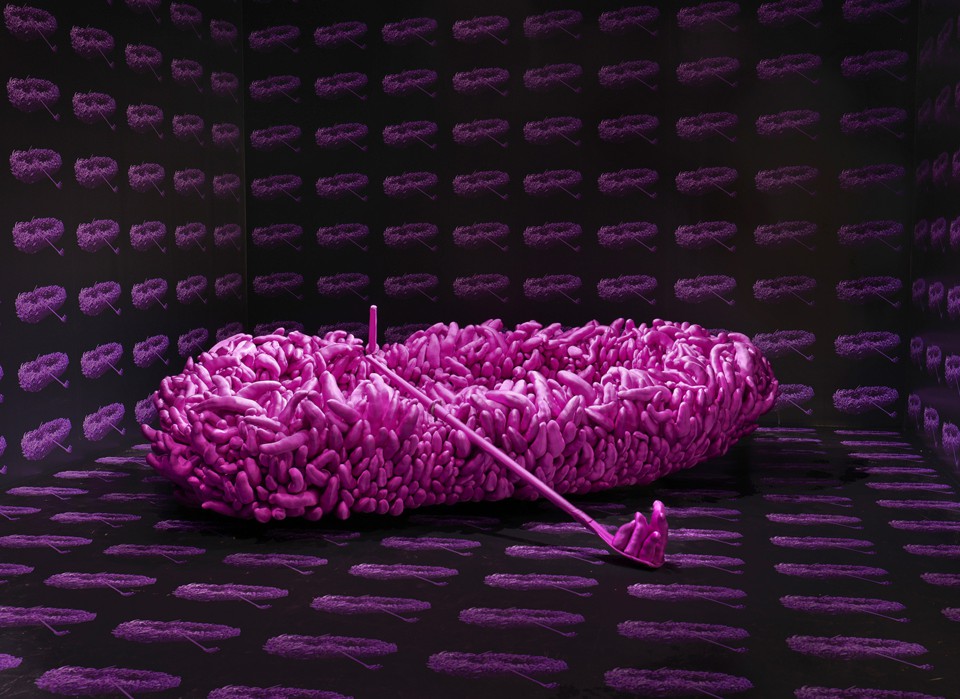

These ridiculous objects, simultaneously comic and tragic, are the perfect warm-up act for the main show, the six Infinity Mirror rooms. The first room, Phalli’s Field (1965/2016), is, if you’ll excuse the expression, Kusama’s seminal work, the bridge between the polka dots and the phalluses. It is also the bridge between Kusama’s New York experiments of the ’60s and her more recent mirrored works. The precursor to Phalli’s Field had no mirrors. It was a carpet of soft phalluses on which she could lie and be photographed. But after growing weary of sewing thousands of stuffed phalluses, she happened on the brilliant idea of achieving repetition with mirrors.

A version of Phalli’s Field was incorporated into Kusama’s public performances. She lolled in the field of her fabric phalluses on 14th Street while a camera captured the scene. Kusama’s work fit right in with the art events that were proliferating at the time—mostly one-off performances, part art and part theater, many of them involving nudity and paint, poetry and music, destruction and silence. They were called “Happenings.” (The painter and performance-art pioneer Allan Kaprow came up with the term in the late 1950s.)

Let me immerse you

in my immersive experience—not that it’s any substitute for being there

yourself. Before we start, I should tell you that your experience will

certainly be different from mine; I was lucky enough to go during a

press opening, so I didn’t have to stand in any lines, I got to enter

each room alone, and I was granted not just 20 to 30 seconds, but a full

minute!

An attendant waved me into the mirrored room that is Phalli’s Field.

As I walked down a short plank leading to the edge of what looked like

an endless pasture of red-and-white polka-dotted phalluses, the

attendant shut the door behind me. For a second, as I became aware of

myself in the mirrors, I had the sensation of being in a department

store’s changing room. But I had choices to make, and quickly. I could

stand there and confront myself in this field of phalluses, or perhaps I

could try to cancel myself out of the space by ducking. Neither felt

right. I knelt on the little dock and regarded myself at roughly the

height of the blooming polka-dot things (mushrooms without caps!). I

confronted myself many times over in many mirrors in this crazy

landscape. Before the attendant came to usher me out, I snapped a

picture or two on my cellphone, and did a quick video-pan around the

place.My next stop was Love Forever, a room that is mirrored on both the inside and the outside—my chance to be a peeping Tom, or rather a peeping Yayoi, if only for a minute. This six-sided chamber—first constructed in 1966, in part as a protest against the Vietnam War—was then reconstructed in 1994, and seems to hark back to Kusama’s childhood trauma. Instead of entering, you peer into it while another voyeur, catty-corner to you, can peer in at the same time. The room is radiant, and literally hot, because of the lights inside it. Although the view you have is abstract—an infinite hexagonal pattern of colored lights that reminded me of old Broadway—it also feels a bit dirty and illicit. You are aware of the reflection of your own eyes across the room and also of the eyes of whoever else is gazing into the box at the same time. It’s embarrassing by design. The viewer is the voyeur, and the voyeur is you.

The present never ends …I was pushed out of my reverie by a jumble of gigantic spotted pink-and-black beach balls beckoning like carnival barkers toward the next Kusama ride. Dots Obsession—Love Transformed Into Dots, first made in 2007, was crammed with more beach balls. I quickly moved through this experience, which was as unethereal as you’ll get from Kusama—Kusama silly. Kusama psychedelic. Kusama Lite.

I become a stone

Not in time eternal

But in the present that transpires

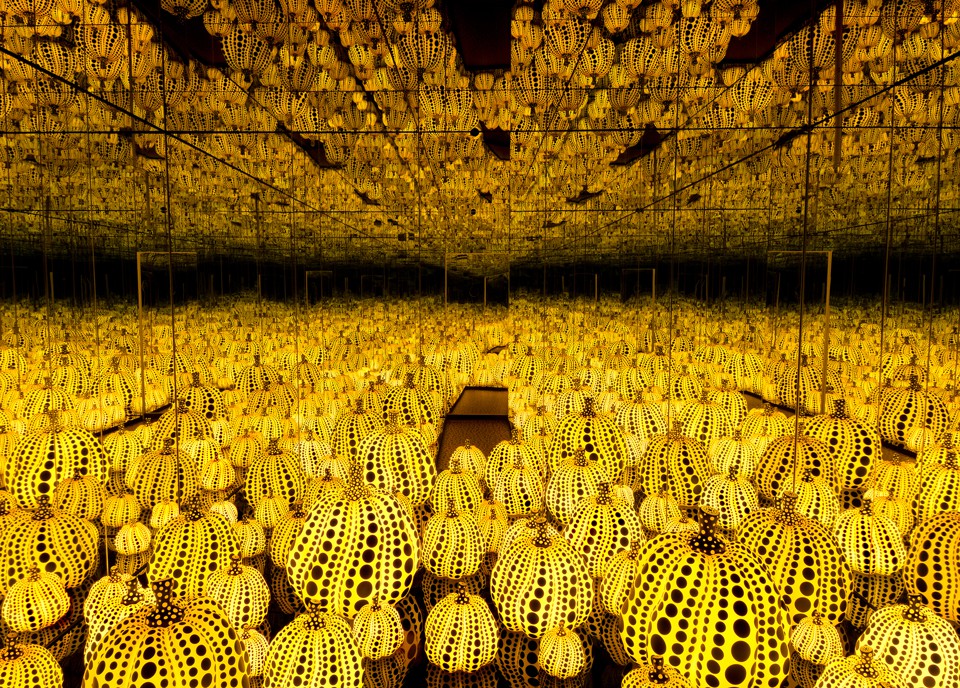

And so I walked beside a field of yellow-and-black polka-dotted tentacles and on to the very last Infinity Mirror room, All the Eternal Love I Have for the Pumpkins (2016). I was conscious of the stark difference between what was above—a stormy sky, looming with dark and dangerous pumpkins—and what surrounded me at ground level: a field of happy, gleaming yellow pumpkins with black spots on them. Was I a faithful Linus shivering at night in the darkness, waiting for the Great Pumpkin? No. As I again viewed myself on the horizon line, I saw that I had become a bridge between two realms, up and down. I was an upright, rectilinear self in a world of orbs.

With its surreal backdrop, the pumpkin room was, I noticed, perfect for selfies. Well, who was I not to take a picture? I snapped 10 or so, and because the pumpkins were even more photogenic without me, once again I tried to expunge myself from some of the photos by lying low. (I learned only after seeing the show that lying down is prohibited.) Then my time was up.

People who know that

I have had the Kusama experience look at me like someone who has been

to Mecca. They ask, anxiously, whether it’s worth it. Should they take

extraordinary measures to get to this exhibit on its two-year-long tour?

As I’ve thought about how to respond, I’ve also been puzzling over the

peculiarities of our particular art moment: Why has the apprehension of

art become so like theater? And why is Kusama, who never received as

much attention in the 1960s as many of her contemporaries did, finally

in the spotlight now?

By offering up to the public the solo art experience that was once her own private world—a primal and personal space for looking and healing and thinking about one’s own place in the cosmos—and then by also allowing selfies in it, Kusama has created the perfect art experience for the social-media age.

Her shows are crowded because, as many viewers will tell you, you really do have to see these works in person to appreciate them. No photograph, however good, can deliver that existential jolt of being there, seeing yourself repeated ad infinitum. At the same time, Instagram is helping to drive Kusama’s popularity; it is the means by which people advertise to the world that they are among the precious few who have had this lonely experience of being one dot among millions. The visual proof has helped propel Kusama’s work to the forefront of destination art in its latest form.

Now the magnet has moved again. Museums and galleries are currently trying to attract visitors by engineering immersive environments and interactions. From Kusama on the grand end of the scale, offerings extend down to the circumscribed and understated: In “Sara Berman’s Closet,” at the Met, Maira Kalman, with her son, Alex, has re-created her mother’s closet, holding mostly white clothing. Meanwhile, this summer the Guggenheim in New York is exhibiting Doug Wheeler’s “PSAD Synthetic Desert III.” Installed near the top of the Guggenheim’s spiral, this small show—a “semi-anechoic chamber” filled with beautiful, sound-absorbing foam stalagmites and stalactites—promises visitors in small groups (with timed tickets) the experience of the silence of the desert.

I went in, took a picture of the gold toilet, sat down, and tried to get a selfie that included both me and the work of art. From the sink, after washing my hands, I got another picture of the gold toilet, alone. And I suddenly understood that, taken in the right spirit, America is not just a riff on Duchamp’s infamous Fountain—a porcelain urinal signed with the name R. Mutt, which, by the way, is 100 years old this year. It is also a supreme example of relational aesthetics, whose core idea is that the give-and-take of a social situation can itself be a work of art. You donate pee, you take away a photo. What will your photo be? Your face as you sit on the gold toilet? Your contribution to the gold toilet? It’s up to you! (I was told that one employee had been fired for standing on the toilet in an attempt to get a good selfie, which he then sent out to his friends.)

If you look around

you, you’ll see examples of relational aesthetics everywhere. Over the

past few years, for instance, several museums have offered up Yoko Ono’s

Wish Tree, on which people can hang their wishes, written on

little paper tags. Recently the Jewish Museum, in New York, hosted “Take

Me (I’m Yours),” in which visitors were supposed to take whatever they

wanted from the exhibition—plaster casts of coffee lids, ribbons with

slogans, buttons, T-shirts, clips of film, vials of air.

In our

trophy-getting, Instagramming, participatory era, the taking and posting

of selfies has become an important and unintentional extension of

relational aesthetics. Whether spectators are invited to take pictures

or not (cellphones are not allowed, for instance, in Wheeler’s silence

chamber), many visitors now experience museums and galleries with a

cellphone in hand and a Snapchat, Instagram, or Facebook account at the

ready. You take a picture, you post it for your friends, and they

receive the favor, and do the same in return.Indeed, some museums have started loosening up their rules about photography, on the theory that people are more inclined to come if they are allowed to take pictures. Regardless of the rules, though, viewers snap and viewers chat, and the resulting experience is hard for any museum to control or to script—which is, after all, a basic (and potentially unnerving) principle of participatory art.

Will Kusama’s exhibition—where photography is obviously welcome—suffer similar indignities? It already has. One visitor to All the Eternal Love I Have for the Pumpkins reportedly tripped over one of the gleaming pumpkins and damaged it while trying to capture a self-portrait in a mirror. What has become almost laughably clear is that Kusama’s mirrored investigations into existentialism and infinity have become theaters of infinite narcissism.

But does it really matter? Narcissism, after all, is one of the inescapable ingredients of participatory art, which not only highlights the give-and-take involved in any art experience, but also calls attention to the power of the audience to complete, or complicate, or confound an artist’s intention. Like Gonzalez-Torres’s pile of candy, Kusama’s works were created, at least in part, to deal with personal trauma, but they are also asking viewers to have their own experience. Surely Gonzalez-Torres knew that some visitors wouldn’t be thinking about aids while sucking the pieces of candy they took from his pile, and surely Kusama knew that no one would experience her works as she did.

Although you may have missed your shot to see the exhibit in Washington, D.C., Kusama will be coming soon to a city that might be somewhere near you: Seattle, Los Angeles, Toronto, Cleveland, and Atlanta. If you ask me, I would say go ahead and put it on your art bucket list. Why miss out on the chance, before you die, to wander through fields of phalluses and polka dots and watch yourself contemplate your own insignificance in the universe? The experience is well worth it, if only to get an intimation of where every bucket list points—to the finitude of your existence in this infinite cosmos. You wait in line, you get your turn, you look around in awe, you snap a few pictures, and then, like everyone else, you are escorted out.

Well, that’s life. It may look infinite, but you are not. You are just a dot, there and then not.

Comments